WEEK FIVE: MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

More than anything, I needed a machete. On the banks of McDonald Lake, the vegetation had sucked up the extra daylight from the summer solstice and exploded across the trail to the Calowahcan Basin. Spiny devil’s club and wild rose brambles tore at my skin, and I had to walk with my hiking poles outthrust to part the sea of undergrowth.

I nearly stepped in fresh bear scat, which made me wary about accidentally startling one of the beasts. The local Salish and Kootenai Tribes had created a Grizzly Bear Conservation Zone on the other side of the lake, protecting the ladybugs and cutworm moths that grizzlies devour by the hundreds of thousands in late summer. The moths congregate beneath rockslides above timberline and emerge at night to sip nectar from wildflowers. During the daytime, bears will dig through the rocks and can eat 40,000 moths in a day. Each tiny moth body is about 70% fat, making them a potent, calorie-rich food source for the grizzlies.

But this time of year, in the absence of moths and ladybugs, bears are not likely to be found above treeline. The Conservation Zone nearby wouldn’t contain them. They could be anywhere in this part of the Montana Rockies, and despite my skinny frame and low fat content, I might make a tempting meal for a particularly fearless predator.

That reality was pointed out to me by two Native American youth that I bumped into on the trail.

“You’re by yourself?”

“Yep. Just me.”

“Why don’t you have bear spray?”

The question seemed almost accusatory. I mentioned the expense and the possibility of “taking friendly fire”, after which one of the kids grinned and boasted that he’d accidentally sprayed himself three different times.

Finally, I admitted that I liked being a bit vulnerable. I wouldn’t want to be completely safe, because then I’d be experiencing nature as more of a tourist than an active participant. I liked being integrated into the whole system of predator and prey… of having to provide for my own food, water and shelter, and in their absence, being responsible for the consequences. On the whole, the logistics of wilderness survival are a lot simpler than the accommodations we make to fit in within Western civilization.

Despite my bravado, I hoped I wouldn’t have to jab a bear in the eye with a hiking pole anytime soon. The two teens accepted my answers and continued on their way. I resumed my upward journey, heading deeper into the Mission Mountains towards a collection of alpine lakes. As I gained elevation, the hands of time seemed to spin backwards, pulling the landscape from summer back into the early days of spring. The plant life lost its photosynthetic vigor and began to shrink down into the soil. White wands heavy with beargrass flowers shortened inch by inch and disappeared entirely. Fresh willow leaves pulled back into their buds and hid. Patches of dirty snow appeared suddenly, multiplied and enveloped parts of the forest.

By the time I approached Summit Lake, I began to worry that I wouldn’t find a dry campsite until summer got around to reclaiming the high country. My fears only deepened when the trail led me to a puddle the size of a small swimming pool. I could see the path continue beneath the waters, and as I looked closer, I was instantly repulsed by a scene that could have been pulled from a horror movie.

Sections of water were literally black with the bodies of tens of thousands of mosquito larvae hanging from the surface. These half-inch cylinders of skin and fuzz wriggled down and away when I came too close. The larvae siphoned oxygen from the air and actually helped filter the water by eating algae, bacteria and other microbes. But I was worried about what would happen in a few days’ time when the mosquitoes pupated and began to hatch. The legions of hell would be unleashed upon the denizens of Summit Lake. I listened nervously for their telltale high-pitched whine, wondering if camping here was such a good idea after all. Hopefully I hadn’t awakened them and triggered some kind of accelerated maturation process. At least the local trout would soon be happy.

I detoured around the breeding pit and found a campsite on higher ground above the southern shore. Summit Lake held a dramatic position beneath Eagle Pass and the towering face of Mount Calowahcan. Submerged shelves of rock were scattered throughout the shallows, and from a distance they looked like the remnants of an Atlantean city.

A logjam blocked the outlet of the lake, and dozens of trout lurked within the labyrinth of tree trunks, waiting to ambush anything tasty that might try to exit the pond. As I balanced on a log and dunked a washcloth in the moving water, I wished I’d brought a fishing pole with me. Then again, I’d seen a pole snapped in half along the trail, and with all the overgrowth and deadfall, I doubt that mine would have survived the journey.

A blob of grey fur with a rat-like tail dashed onto the logjam bridge while I was washing up. I think we noticed each other at the same time, but the meadow vole was quite shocked by my presence. It immediately slipped on a log, crashed full speed into the water and disappeared. I wondered where it had gone… perhaps snatched up by a hungry trout. Surprisingly, the rodent managed to swim the remaining distance under the logjam. It sprung from the water on the other side of the outlet and, without bothering to shake itself off, sprinted to the safety of a pile of boulders.

I lit a fire that evening, just in case the mosquitoes decided to speed up the hatching process for my sake. They didn’t, but I was woken up twice during the night by other voracious animals. Some rodent – perhaps that very same meadow vole - tried to chew its way into my tent to sample my trail food. I finally wised up and triple-bagged my snacks so the smell wouldn’t be so attractive. Should’ve been following that policy anyway, camping in grizzly country.

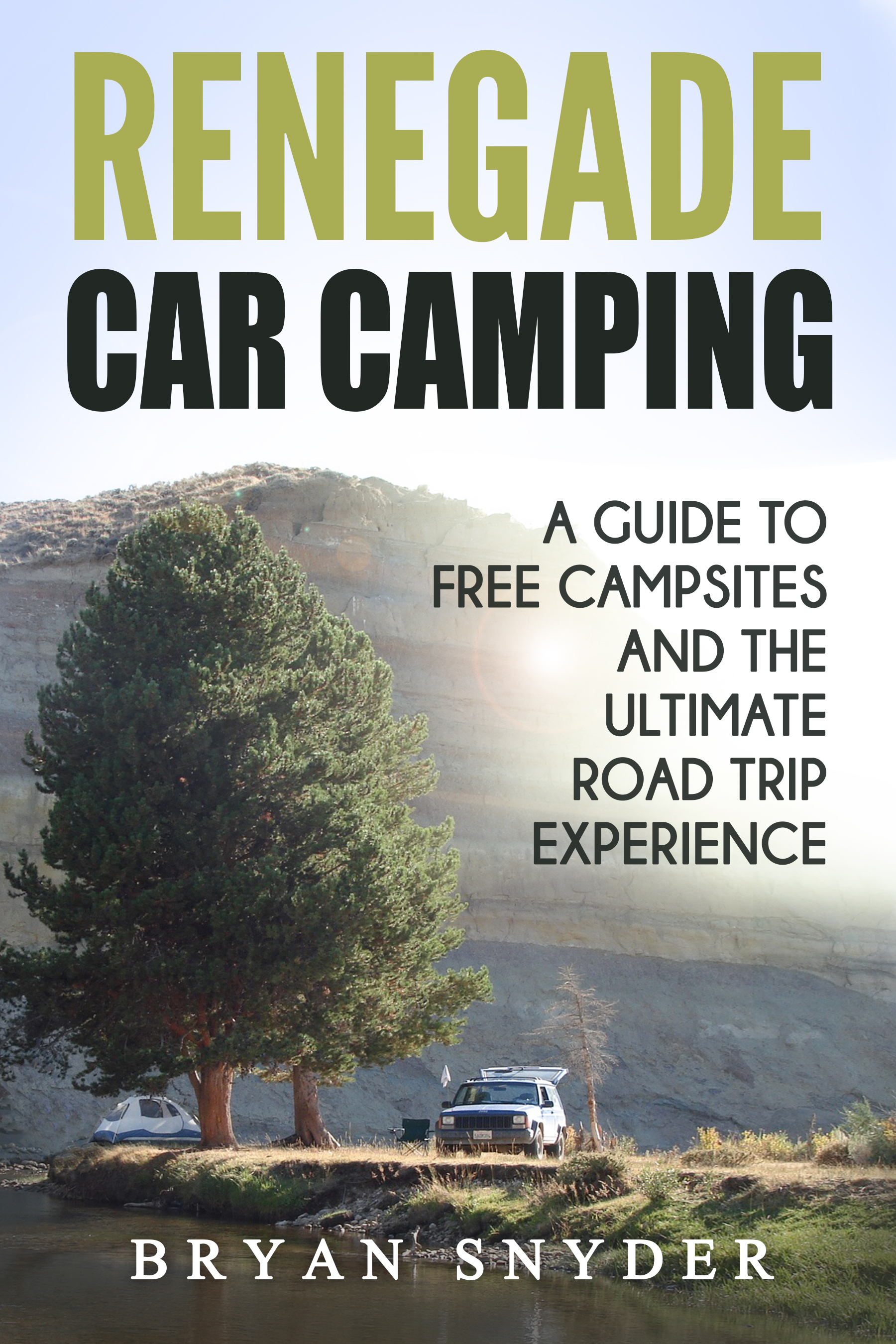

In the morning, I climbed Eagle Pass and scaled Calowahcan’s south summit to get a good view of the rest of the Mission Range. Somewhere to the west on the Flathead Reservation lay a 120-year-old church and the remnants of the Catholic mission that gave these mountains their name. My own mission, so to speak, was nearly complete. I dropped 5,500 feet in the next four hours, my downward momentum helping me plow through the dense vegetation. Despite losing the overgrown trail several times, I managed to regain my bearings and bushwhack across to Lake McDonald to reunite with my jeep once more.

In my absence, the vehicle had been invaded… by mice. The little vermin had nibbled away at a cache of granola bars and peaches, leaving behind a dismaying number of fecal droppings. They’d even taken a napkin and begun to build a shredded nest beneath the back seat. I should have known better than to leave food at a trailhead, too. As I always suspected, it’s the littlest creatures – not the thousand-pound giants - that you really have to keep an eye on.